I was asked to contribute a chapter in a book on “change”. It is now published. In Lessons on change, 15 creative minds have their say and show how they are tackling the changes of our time—through art, new narratives, and innovative economic models.

You can read my contribution, slightly amended, below.

I think the first awakening about environmental issues was when my mother explained the link between detergents and the algal bloom in the lake at my grandparents’ place where I spent my summers up to the age of eleven. Quite early, I also reacted on how cars polluted the environment and how many people were killed or maimed. Together with my best friend, I became engaged in a bicycle activist group in our home town, Uppsala, at the age of thirteen. The group organized political demonstrations and collected names for petitions against parking garages and new roads and, quite rapidly, we became core activist together with much older people - which when you are thirteen means that they were twenty.

Through the protests against the war in Vietnam I also became more interested in general politics with an anarchist inclination. Meanwhile, the environmental interest continued with an increased focus on nuclear power. Protests against nuclear power were intense and led to a moratorium of new nuclear power in Sweden 1980. The decision also implied that the existing reactors should close down but that never happened, some of them are running now almost 44 years later.

At the age of eighteen, I had come to the conclusion that it wasn’t enough just to protest. There was a need to develop real life solutions to both the environmental and social crises, preferably at the same time. I met like minded people and we started to plan for the establishment of an agrarian commune with the focus of social development and environmental friendly technologies. As we had realised the enormous corruptive forces of the dominant society, far reaching self-sufficiency was also part of the plan.

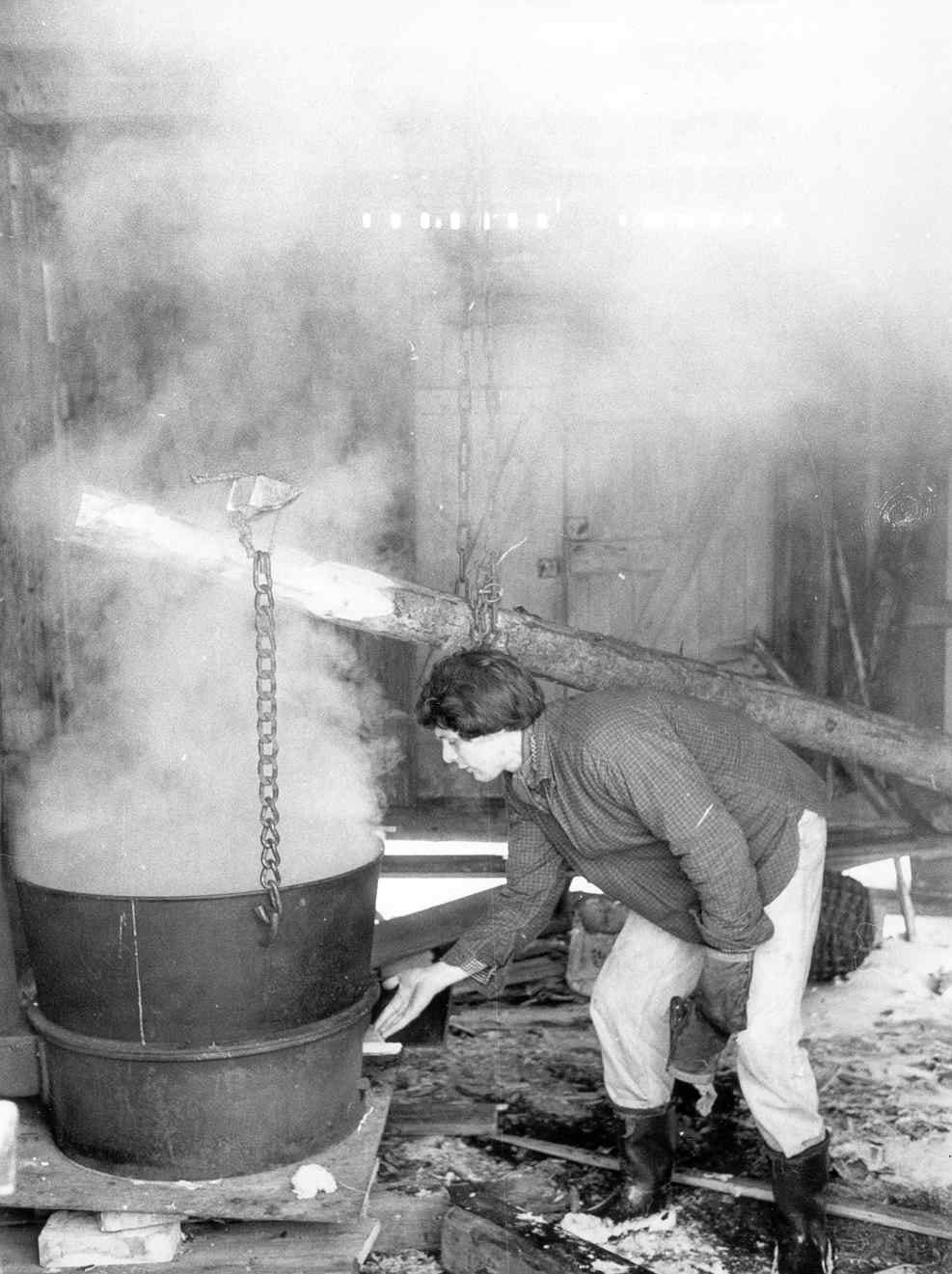

It took some time, but in February 1977 the five of us could move into the Torfolk farm in the middle of Värmland, a county in Sweden. The first years we spend on learning all the necessary skills for a fairly self-sufficient life, including not only growing crops and tending to animals but also things like tanning moose hide, making cheese and butter, logging, knitting and weaving. We had a horse for work in the forest and for some of the agriculture work. One of the people had an agriculture education, another had some skills in welding, and a third in weaving. I had some inspiration and knowledge from my mother who was a trained “country household teacher”, an education for taking care of livestock and crops and process them into food. My father was almost a caricature professor who neither could handle a hammer nor fry an egg.

My life companion at the time, Kari, got a job in the municipality to get us some cash income to pay the mortgage we had to take and pay for the investments. For the rest we lived on a small shoestring budget. Initially, we also had plans to grow the commune and received visitors with open arms. Many young people were searching for alternatives at that time (hippies and a “green wave” of back-to-the land) and we had many visitors, some stayed a week, some several month. Some of the founders left and some new came in. After some years we got tired of the flux and became much more restrictive on taking in new members even though we never closed the opportunity. For many years we were five and then for almost twenty years we were two couples.

In some regards, we were very communitarian and shared all the income and each one used our common funds at their own responsibility. As we had so little this didn’t pose any problem. When children grew up, they got pocket money. My experience is that it is a bigger problem when there is more money around and people may want to go for holidays, buy fancy things or visit a rock concert. We had no leader and had almost never any formal meetings; decision making was at the dinner table. We also had no agreed written down plan for what we wanted to accomplish or how we wanted to do it. On the personal relationship and emotional front we were more traditional, we rarely discussed our feelings.

Over time, our orientation changed and we abandoned the radical self-sufficiency and developed some income generating activities, starting with goat farming and cheese making and the growing of vegetables. This was not a result of any formal decision making but more of a gradual shift. The reasons were, as I recall it, among others the feeling that by distancing us too much from society at large we also lost many opportunities for interaction and changes. Just being a (freak?) example wouldn’t change much. I and my life companion at the time also got the first child 1980 and when you have children you also need to consider that your choices also are imposed on them. When the children have friends, peer pressure mounts to have similar things, do similar things and even believe in similar things. When your child watch TV at a friends you will sooner or later have to buy a set of your own. We also wanted a bit more comfort and things like washing machines and chain saws.

In addition, we were probably victims of the change of winds in the eighties with more focus on self-fulfilment and ideas that you actually could change the system from within. Even if we didn’t embrace the emerging neo-liberalism at all, it was hard not to be influenced by it as with any other prevailing societal trend. We thought that you could make a living and still make things in a small-scale and nice way if you just did it smartly enough. We embarked on the construction and use of smart small scale technologies for vegetable production and cheese making in order to be competitive.

Already from the onset we grew organically, even if we followed no special organic method or had any kind of certification. In Sweden at that time, the term normally used for organic was either poison-free farming or bio-dynamic farming (which was used as a generic term not linked to the special bio-dynamic method). Since the early 1990s the term ”ekologisk” (ecological) is used. When we tried to market our growing vegetable production to the regional supermarkets they came back with a certain interest, especially the consumer cooperative Konsum (now Coop) supermarkets as they had decisions from their membership assembly that they should start to sell organic products. In order to be an attractive supplier we needed to have a regular supply of a wider range of vegetables. We rallied together a handful of organic growers and created a marketing cooperative, Samodlarna, for sales of organic vegetables to supermarkets, to my knowledge the first of its kind in Europe, 1983. We established some simple rules to be followed by the members and we got the regional advisory service to allocate a person to verify that our members followed the rules, a rudimentary certification system. Our farm managed the marketing and administration of the organization.

The cooperative was successful and got a lot of attention. Our example spread and in winter 1984, we collected like-minded people from other parts of Sweden for a few gatherings where we discussed how to progress organic agriculture. At this time the early organic pioneers (mostly biodynamic) had been joined by a group of more politically interested and environmentally motivated “back-to-the-landers” like ourselves. The meetings resulted in a three pronged institutional strategy for the organic movement with a national marketing association to further the organic market, an ecological farmers association to pursue the political acceptance and support of organic and further organic knowledge and the formation of a certification body, KRAV, 1985. I became the first executive director of the organization and commuted (7 hours by bus and train) on a weekly basis between the farm and the KRAV office in Uppsala.

KRAV was founded by three organic associations but already at the onset the idea was to engage member organizations representing the whole food chain as well as environmental organizations and animal welfare group. The reasons for this was to augment the credibility of the organization and the certification as an impartial service as well as to ensure the support from the members for the KRAV-mark and organic products. The role of KRAV was to formulate organic standards and to inspect and verify that affiliated farmers and food producers followed the standards. In addition, KRAV informed the public and promoted organic products in a generic sense.

In the process of establishing KRAV we also looked outside of Sweden to see how people had organized organic certification in other places and got inspiration from organizations such as Nature et Progrès in France (which two of us visited 1988), Soil Association in the UK and California Certified Organic Farmers. We also realized that we had common needs with these like-minded organizations in how to further progress organic standards and certification and how to verify that organic standards were followed etc. This led me to the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, IFOAM, founded 1972. There I got involved in the development of a global organic guarantee system (IFOAM 2024) with the ambition to safeguard the integrity of organic products. In 1993, I became the chairperson of the IFOAM accreditation program, later becoming the International Organic Accreditation Services with the purpose of ensuring the quality of organic certification world-wide.

In a parallel development, the EU adopted a regulation for the marketing of organic products in 1992. Also the United States was in the process of doing so. It is often claimed that the regulations were developed to protect the consumers, but it is worth noting that there were hardly any consumer organizations demanding the regulation. The initiative to regulate clearly came from the producers and their desire to have a ”level playing field” in the market in particular from France and Germany where the sector was very fragmented. Most of the organic sector supported this development for three reasons: the general recognition of the relevance of organic agriculture which is implicit in a regulation; the increased possibility to get government support for organic production and organic market development, and; the lack of trust among organic sector actors, both nationally and internationally. This last point had to do with that in most countries there were many competing organic associations and certification bodies which often slandered each other leading to suspicion also in the public. Our experiences in Sweden with one unifying independent certification scheme with a high level of public trust made me opposed to any regulation as I feared that the definition of organic would be overtaken by government, which later also happened. I failed, however, to convince the majority of the organic sector that government regulations was a bad thing.

As a result of the success of KRAV and my involvement in IFOAM, I got a lot of requests to help in the establishment of national certification bodies and organic developments in other countries and from 1995 onwards I established the Grolink consultancy which grew rapidly and at its height around 2006 had a dozen associates, a turnover of SEK 35 million (approximately EUR 3.5 million) and worked in most continents.

Even though some of the core business was to help in the establishment of organic certification bodies I gradually lost the interest in certification as it had passed a pioneering space and been overtaken by regulations. Also within the organic sector I often found myself in opposition to those who demanded stricter and more detailed standards and certification rules. The rigidity of the system also stifled innovation, experimentation and local adaptation, essential aspects of evolutionary change. In addition, it transferred most of “the ownership” of the organic project to governments and organocrats (those with a full time job to control the system). The rules also included provisions that prohibited certification bodies to assist producers in compliance and to be active in promotion of organic products. Certification was, therefore, gradually taken over by professional multinational companies, and the sector in total spent a lot more resources on demonstrating that it was reliable and trustworthy than in helping farmers or developing the market.

Perhaps this was inevitable, but I was more interested in things that would lead to development rather than trying to limit and restrict the sector. Gradually I shifted my focus, both as a consultant and as an organic activist, towards marketing, policy development and alike. In 2002-2008, Grolink managed a very successful project for organic exports from Africa, EPOPA which gave more than 100,000 smallholder farmers access to organic markets (Rundgren 2008). It also managed an international training programme for the organic agriculture sector in developing countries which trained existing or presumptive sector leaders.

I was elected vice-President of IFOAM 1998 and I was the president 2000-2005. During my term we initiated many policy processes and tried to position organic in the context of the Millennium Development Goals (the precursor to the Sustainable Development Goals). We also promoted participatory certification and group certification as alternatives to commercial certification. As the organic sector had been dominated by certification, standards and market development, IFOAM also initiated a process to define and highlight the wider agenda embedded in organic agriculture. One of the accomplishments that I am particularly proud of were the development of the Principles of Organic Agriculture. They represent somewhat of a step back towards the roots of organic, emphasising that organic is much more than a market oriented production method.

The Principles of Organic Agriculture

Principle of Health. Organic agriculture should sustain and enhance the health of soil, plant, animal, human and planet as one and indivisible.

Principle of Ecology. Organic agriculture should be based on living ecological systems and cycles, work with them, emulate them and help sustain them.

Principle of Fairness. Organic agriculture should build on relationships that ensure fairness with regard to the common environment and life opportunities.

Principle of Care. Organic agriculture should be managed in a precautionary and responsible manner to protect the health and well-being of current and future generations and the environment. (IFOAM 2023)The years as an international consultant and IFOAM president took its toll. At the peak around 2005, I was constantly travelling and spend most of my time on the road, or in the air. I also had the feeling that I had done what I could in the organic sector and that “organic” as a concept for bringing change also had some severe limitations. I observed that through the market success and trying to be relevant by adjusting the narrative to mainstream agendas, organic lost some of its transformative powers. The same market forces that drives larger scale and monocultures in conventional agriculture also became more visible in organic agriculture.

During this whole time I still lived on the farm, I had, however, lost some of the engagement in it. This was also self-generating as I had the opinion that it was those that actually did the work that should decide what and how to do it. The farm had also during my many years of semi-absence embarked on new ventures which I was somewhat less interested in, such as a jam-making business. Also the vegetable production had expanded considerably and became larger scale and less diverse. This also meant that we became structurally dependent on hired labour, which had big implications. When you work for yourself, you still need to make ends meet and pay all your costs as well as getting remuneration for the time spent. But it is still up to you at any given time how you go about it. When you have hired labour you inevitably must focus on productivity of labour as the workers must earn their salary most of the time. You are also confronted with the fact that some people work better and other less well and you are forced to seek those with higher work efficiency. Another aspect that changed with hired labour was that our very informal way of management didn’t work – the employees were not present at the dinner table. And in any case, they were more interested in clear management structures than participatory workplace democracy. At one point in time, we suggested that the jam-making business should be converted to a workers’ cooperative, but the staff was not interested as they realized they would have to take more responsibility, work more and earn less.

I had the typical mid-life crisis, questioning my purpose, what I did and how I did it as well as the relationship with my life companion. I took a time out of almost half a year in 2007/2008, bicycling my way through the Baltic states, Poland, Ukraine, Turkey, Greece, Italy, France and Switzerland where my time and money was up and I took the train home. I moved out of the farm, even if I miss both the place itself and the companionship and friendship to this day.

Already at a young age, I was very interested in the big picture developments, trying to understand what was wrong and what was good in the world. For more than 30 years I had been involved in practical action, appropriate technology, organic farming and other ways of making a change here and now with an emphasis in organizational work. I still think that is a commendable thing to do, but sometimes you also get a bit lost in the short-term issues. A case in point is my work of linking small-holders to export markets. Certainly that gave them a somewhat higher income, and when people earn just a few hundred dollars per year that is good. But I got less and less convinced that integration into (unreliable) global markets is the best way ahead for small farm development. In the end, there will be a limited number of well-resourced farmers that will reap the benefits. Increasing exports of high-value crops mostly also means increasing imports of staple foods, which is a risky strategy and leads both farmers and countries away from self-determination.

During my trip, I started writing in an effort to summarize my view of the world. It resulted in a book published in Swedish 2010 and in English 2012 (Garden Earth- from hunter and gatherers to global capitalism and thereafter). In 2011 I wrote yet another book with my wife to be, Ann-Helen. This was followed by three more books, one on my own and two with Ann-Helen. The books are in different ways about the modern civilization and its relationship to the natural world, often with a focus on food and agriculture, both because it is my core area of expertise and because it is the most important way we interact with the rest of the natural world for the better and the worse.

In 2014, we bought a small farm outside of Uppsala. The plan was mostly to grow vegetables and plant fruit and nut trees on smaller scale. The farm was a bit bigger than our plans and had 40 hectares of forested land and far more cropland than we needed. Most of the cropland was very low-lying and frequently flooded by the lake and in permanent grass. In the end, we realised that grazing and hay was the best way to produce food from that land. We restored some 10 hectares of former grassland that had been spontaneously reforested. In Sweden, semi-natural grasslands, are biodiversity hotspots but the last century at least ninety percent has been abandoned, mostly converted to plantation forests of little value for bio-diversity.

For the management of the land, we bought some cows and established a small herd of mother cows with off-spring. This coincided in time with a huge increase of veganism and a media view of cows as being climate killers on par with, or even worse than, cars and aeroplanes. We considered that there were flaws in the scientific basis for many of the claims and that other claims were applicable for some kinds of livestock keeping but not others. In addition, we realized that there was little understanding of the long term partnership between man and cattle, sheep and other grazing animals, the cultural values, the contribution to a sustainable food system and alike. So we wrote a book about cows, Kornas planet (The Planet of the Cows) which was well received. The book was the result of us buying cows which was caused by the conditions on the farm we bought and that we bought that particular farm was to a large extent a coincidence.

Also our latest book, Det levande 2023 (The living), was a result of us participating in the public debate about food, agriculture, forestry and environment. We realised that in the view of some, all human use of nature is by definition harmful. This means that the way forward is to limit this as much as possible and to produce food in industrial processes, abolish livestock, don’t use firewood etc.1 Others, still the dominant narrative, see nature just a mine to be extracted and are convinced that we can find technological solutions to all problems we create, preferably with market mechanisms. This means that there are underlying assumptions and world-views that needs to be brought into the open and discussed before we even can have a meaningful conversation about farming, bio-diversity and climate. We promote a view of an active relationship between humanity and the rest of the living, where our lives should be geared into positive contributions to bio-diversity. Parallel to the writing of books, I do some consultancy job but mostly in Sweden and give quite a lot of lectures, Ann-Helen works as a journalist and we both engage in the development of the farm.

Based on my experience with Torfolk, the organic market, small holders in Africa and the general development of the food market, I have come to the conclusion that the market mechanism itself is problematic as it reduces food and agriculture to products to be sold and the land itself to commodity. On our farm, we want to work with relationships instead of transaction as the leading principle. Relationship food is based on personal relationship between those that produce and those that consume and the management of the farm is a relationship between us and nature, formulated somewhat idealistic. Food is in this way an expression of these relationships. The meat we produce is all sold directly to consumers, many of which live close by and can see our cows. The vegetables are sold in Reko-rings (Isaksson et al 2020) and Ann-Helen is an administrator of the ring in Uppsala. Reko-rings have some similarities with food assemblies/Märktschwärmer/la Ruche qui di oui. The Torfolk farm has also moved in that direction. Instead of using the market as a tool to change things for the better such as with organic certification, this strategy aims to reduce the power of the market and replace it with relationships, even if money still often is used. In addition, we want to develop other non-market mechanisms based on foods as commons (Rundgren 2012, Vivero Pol 2017). We have also lately started to give away food to a charity for homeless people. This is of course facilitated by the fact that we have other incomes and that I get a pension since three years.

As the reader probably can note by now, where I have put my energy has not followed a very straight path, but been driven more by coincidences and needs arising from the situations I have been in. It has also oscillated between practical work, organizational work and intellectual and analytical work. I guess that reflects my personality. I am also more of an entrepreneur than a steward despite my theoretical affiliation to stewardship and critical view of the restless innovation and “creative destruction” (as expressed by Schumpeter 1942) of our times. Even if I am, in theory, a stern proponent of community building, trust and relationships, having a very introvert personality means that on a personal level I am not so keen on interacting so much with other people.

I haven’t got a change theory, but I have strong misgivings in many of the ways both society and organizations are managing, or trying to manage, changes today where setting goals and making strategic plans are seen as major tools for change. This is expressed on all levels from the personal (set your own professional goals) to the global (Paris agreement on climate, Sustainable Development Goals). In the field of climate policy it seems like setting long-term strict goals mostly is an excuse for doing very little in a short term. Development projects have been dominated by the latest planning tools and I have spent many work hours on developing logical frameworks (EU 2023) and thereafter spent even more hours in reporting accordingly. Businesses and organizations have spent endless energies on formalised ISO 9000 quality assurance with limited value (Rundgren 2012).

For sure, there are certain things that are best accomplished by setting goals: the landing on the moon comes to mind or completing an education. Plans and goals are useful, but can only be short term guides and need to be regularly revised to accommodate for changes in the environment. Their main value lies in the process of making people reflect on why they do things and why they do it in a certain way, rather than in the end result. In general, personal or social developments do not work in a planned manner. I believe it is more interesting to work following certain principles, values and processes than to work according to goals and plans.

It is also important to realize that humanity is not as much in control as we (mostly) wish to believe and that many developments are caused by changes in the external environment. This means that adaptability and resilience are very important properties on a personal, organizational and societal level. Timing is often critical when it comes to changes. Somethings may be “impossible” at a certain time, but can rapidly become possible or even necessary. The launch of KRAV was clearly made at an appropriate time. But timing is difficult and cannot mostly be planned. This means that a certain opportunism is valuable.

When designing strategies for change, it is important to work with methods and means that in themselves embed the ends and goals. If you believe, like I do, that capitalism as a system is harmful, that food and agriculture should be commons and that humanity should leave more space to other species while at the same time be a responsible keystone species, then the short and medium term actions and political demands should contribute to the reality you desire. As an example, using market instruments (e.g. tradeable carbon sequestration credits) for combating climate change might have some short term benefits as it is simple and can be implemented within the dominating market framework. Such schemes will, however, increase the reach of capitalism and lead to commodification of even more parts of human-nature relationship – the opposite of the desired development. Increasing self- provisioning by communities takes chunks of our lives out of the market and will at the same time lead to less consumption and less emissions as self-provisioning reduce the time available for salaried work and thereby shrink the economy and human demands on ecosystems. Political demands that make downsizing and market decoupling easier fit into such a strategy. The strategy has some similarities with André Gorz´ as expressed e.g. in the essay Reform and Revolution 1968, even if the context is different. Meanwhile, increasing self- provisioning by communities will change the culture and mindset of people as well as inspire to new forms of self-management and democracy. And it can be done here and now.

References

EU 2023, Logical Framework Approach, https://wikis.ec.europa.eu/display/ExactExternalWiki/Logical+Framework+Approach+-+LFA accessed 30 December 2023.

Gorz, André Reform and Revolution, Vol. 5: Socialist Register 1968.

IFOAM 2023, https://www.ifoam.bio/why-organic/shaping-agriculture/four-principles-organic.

IFOAM 2024, The Organic Guarantee System of IFOAM, https://www.ifoam.bio/our-work/how/standards-certification/organic-guarantee-system.

Isaksson, Filippa and Leijon Cedermark, Marie, 2020. Opportunities for Short Food Supply Chains : attractive communication strategies within a Swedish REKO-ring.

Rover, O.J.; da Silva Pugas, A.; De Gennaro, B.C.; Vittori, F.; Roselli, L. Conventionalization of Organic Agriculture: A Multiple Case Study Analysis in Brazil and Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6580. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166580.

Rundgren, Gunnar 2008, Organic Exports, a way to a better life, EPOPA 2008, 110 pages http://www.grolink.se/epopa/Publications/Epopa-end-book.pdf.

Rundgren, Gunnar 2012, Quality management is a management fad elevated to divinity, The Organic Standard Issue 138, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315113707_A_management_fad_elevated_to_divinity

Rundgren, Gunnar. Food: From Commodity to Commons. J Agric Environ Ethics 29, 103–121 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-015-9590-7

Schumpeter, Joseph, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, 1942, Harper & Brothers.

UN 2023, THE 17 GOALS, https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed 30 December 2023.

Vivero-Pol, Food as Commons or Commodity? Exploring the Links between Normative Valuations and Agency in Food Transition. Sustainability 2017, 9, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030442

1 See for instance George Monbiot’s book Regenesis.

Thanks Gunnar, I feel my life is very similar to yours but my time is limited as I approach 77 years old. I still work with the horses.. in fact I just purchased a pregnant mare which has me worried as I have never had a horse birth on our farm.

While I am not sure that farming is the everything in life it sure makes one realize the difficulties of keeping alive while trying to feed ones self. Caring for animals is a difficult but very rewarding experience. We start at day break about 6 am here and work till 8 or 10 pm at night.

Doing the right thing for the soils, animals birds and nature in general is a life's commitment.

I have yet to figure out how to create community.. we have lots of visitors but I need those that believe in caring for nature and put that first in life.

I had better go and look in on that pregnant mare.. I just introduced her to the three other horses over the last week.... and now I need to learn how to cope with a new born horse!!!!

Life goes on.....