Is 100 years of cheap food coming to an end?

Fossil energy, nitrogen fertilizers, food and labour

This week, Swedes are called to boycott the major retailers in protest of a rapid increase of food prices (they are also supposed to boycott US goods as a protest against trumpism). Retailer say they are not to blame. As there are only three retailer blocks and the biggest of them, ICA has a more than 50 percent market share, many put the blame on them. Naturally. But they push back and say that costs have risen. Not that I have any particular sympathies for them, but in this particular case I have to say they are right. A quick look at last years’ profits show that their profit rates are – for capitalist companies – low, just a few percent. And the food industry in Sweden even made a loss in 2024. Discussing prices, the concentration in retail and food industry is much more problematic from the perspective of the farmers than of the consumers.* In addition, a look at food prices in the EU shows that the food prices in the EU as a whole and in Sweden has kept the same pace over 10 years, with a 40 percent increase since 2015, taking off during the pandemic and getting speed with the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In the US, food prices rose by 23.6 percent from 2020 to 2024 according to USDA statistics. The global supply chains were disrupted 2020 by the Coronavirus pandemic. In 2022, food prices in the USA increased faster than any year since 1979, due in part to the avian influenza outbreak and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. From the outside it is still a bit hard to comprehend that the US government is dishing out support to farmers because of low commodity prices (even more so considering Musk-Trumps radical cuts in government expenditure) when food prices are on the rise. The cost of raw materials, i.e. the stuff that comes from farms, is, however, a minor share of food prices in rich countries.

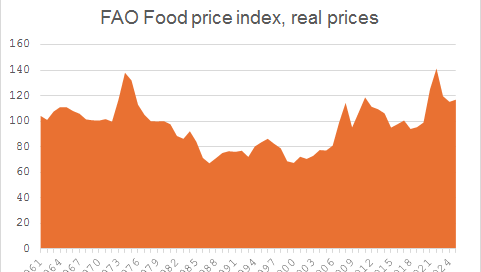

A global look gives a slightly different picture, with a less dramatic increase than in Europe or the USA. It should be noted that the long term (100 year) trend of food prices was falling until around year 2000, albeit with irregular hikes, mostly associated with oil prices. Carey W King writes in the Economic Superorganism that: “in the history of mankind, the cost of energy plus food has never been cheaper than around the year 2000.”

Notably, even if the FAO index is called a food price index it is a commodity index reflecting whole sale prices of a basket of important food commodities and not food products as they are bought and consumed.

Fossil energy, nitrogen fertilizers, food and labour

There are multiple reasons for why food prices are on the rise. There are major similarities between the FAO food price index and energy prices. This is also quite natural as energy is a major input in the whole food system. Transportation costs have increased a lot, which have two consequences. One is simply that costs increase, the other, equally important, is that competition decreases (which mostly leads to higher prices). More than free trade policies, the low cost of transportation has been the main engine for the economic globalization. On the farm input side, nitrogen fertilizers is very energy intensive. The trade in animal feed is huge and stretch over the oceans. On the farms, energy is used for machinery and in the later stages a lot of energy is used for processing, refrigeration etc. The increasing cost for nitrogen fertilizers will lead to both higher costs, but also lower yields as most farmers will reduce the use. This will in turn constrain supply and drive prices upwards. This will have a particularly high impact within the EU because of the combined impact of environmental and climate policies and tariffs (see box). The worsened global security situation has made many countries looking into supporting their own food production, which also comes at a cost compared to the prevailing-buy-cheap-in-world-markets paradigm.

The EU nitrogen trilemma. The EU has a number of policies having an impact on the use of nitrogen fertilizers. There are a number of environmental regulations such as the nitrate directive and the NEC directive (concerning air emissions). Then there is the carbon trading scheme which imposes rather high costs on EU-producers of fertilizers. From next year, also imports of fertilizers will be subject to the new “carbon tariff” (the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, CBAM), which means that imports essentially will be taxed in a similar way as the domestic production.

The EU stopped buying fossil gas via pipeline from Russia, but sanctions don’t apply to LNG from Russia. Perhaps there is some hidden logic here, but it appears to me as some kind of self-inflicted wound as LNG is considerably more expensive than piped gas. As a result of high fossil gas prices, EU fertilizer producers find it hard to compete, in particular with Russian producers that use gas that costs just a fraction of the price in the EU. It is actually so profitable that the Russian government has imposed a special export tax, which has supplied the government with a lot of funds. To cut a long story a bit shorter, the EU is now planning to impose special tariffs on Russian fertilizers.

Predictably, the farmers are protesting. Clearly, all these regulations on nitrogen fertilizers will impact food prices considerably. On the flip side, this will level the playing field for organic farmers and it will reduce nitrogen emissions!The combined effect of higher energy costs and higher human energy (food) costs leads to higher labour costs. Even if the farm sector employ few people these days, the whole food chain has a lot of workers. An estimate by the FAO is that 1.23 billion people are employed in the agriculture and food chain and that almost half of the global population live in households linked agriculture and food chain livelihoods.

In the end you get, from an economic perspective, a vicious circle with high energy prices leading to high food prices leading to high labour costs leading to high distribution costs leading to supply chain disruptions leading to high food prices...

While this will be a great challenge for politics and for the poor, it might also be a start of a rebalancing the food system and the economy towards localized food systems with a higher share of self-sufficiency and ruralization of societies. But that is yet another story.

Climate change?

There is also the possibility that climate change starts to hurt food production. That is certainly a likely outcome in the future, but I am not yet convinced that this is already the case, at least not on a scale that influence global food production and food prices. Most qualified research on the topic discuss future risks and scenarios rather than today’s situation. But even a modest increase of freak weather event can have massive impacts on food prices. As the example of the EU shows, policies to combat climate change might have as high impact on food production as climate change itself. I don’t say that because I think it is wrong to make policies to combat climate change, but I believe it is essential to be clear that those policies, mostly, come with a price tag, which in the short term actually can be quite high as well as painful for those bearing the brunt of the policies, be it farmers or consumers.

* The oligopoly of retailers and food industries are very harmful for the quality of products and for the ability of small farmers and food industries to compete. Big retailers want to buy huge volumes of standardized products, something that a small scale diverse food system can’t (and should not) supply.

In 1950, the year I was born, the average American family spent 20% of its income on food. And eating out was not the significant factor it is now. By the 1980s, when I was in my 30s, the percentage had dropped to 5%, which was maintained until about 2008-2010. In the last 10-15 years, the percentage has crept up to 6%, largely as a result of inflation. Food is still cheap compared to housing and transportation. I have absolutely NO sympathy for retailers because of the corporate takeovers of agriculture. Now, major corporations control the supply chain, so when they whine about their low margins at the retail level, they mask the money they make all along the supply chain. As a sustainable farmer, no one helped me out and I had to basically work for 50 cents/hour. Like many farmers I cashed out my sweat equity when I retired. What really made me economically comfortable - for the first time in my life! - was moving to a cheaper country: France. Nevertheless, I still grow most of our food and this keeps us in good health and allows us to live on our Social Security - something most Americans who still live in the US cannot do.

When you are a small farmer or fisherman you need to find a niche where the big players don’t compete. Rare livestock , high end vegetable crops, out of season production or tasty produce that just won’t ship. Otherwise you are competing with 500 horsepower tractors. When peoples food budget gets reduced they tend to cut back on high end specialties which puts lots of stress on small producers and restaurants. People’s search for value also IMO leads to cheap processed and unhealthy choices . This year I plan to grow several blocks of sweet corn and put together a hot dog cart for the farm stand. If I can’t tempt their desire for quality I guess I will try to appeal to their addictions.